What is Cystoid Macular Degeneration?

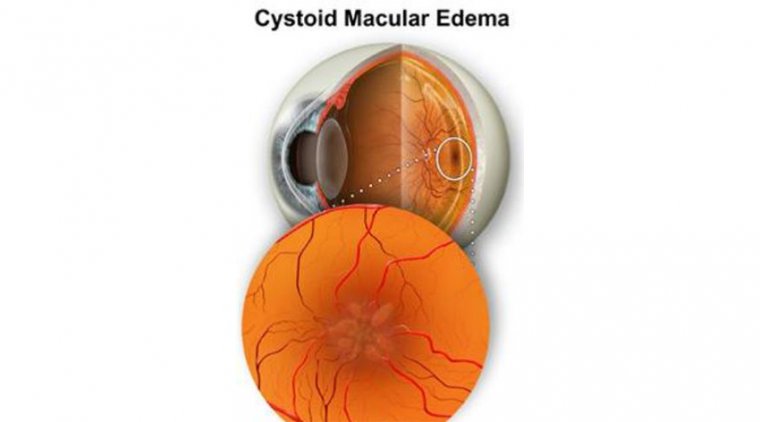

The center retina, or macula, is affected by the painless condition known as cystoid macular edema (CME). When this disorder is present, the macula develops many fluid-filled cyst-like (cystoid) regions that enlarge or inflate the retina.

The most important region for the sharpest vision is the macula, which forms the center of vision. Cystoid macular edema is the name for the disorder in which fluid swells the macula in characteristic cyst-like patterns. The ideal course of treatment for someone with cystoid macular edema can only be advised by an eye specialist.

The eye and the camera are frequently contrasted. A lens in the front of the eye focuses pictures on the rear surface of the eye’s interior. Special nerve cells on this surface, known as the retina, respond to light.

The macula is located in the middle of the retina. Our finest visual acuity is found in the macula, which forms the center of our vision (sharpness). The macula can occasionally swell up because of fluid. Edema is the medical term for when bodily tissues swell due to fluid retention. It is known as cystoid macular edema when this occurs to the macula and the edema fluid often congregates in patterns resembling cysts.

Cystoid macular edema is recognized to have a wide range of causes. These consist of:

- cataract surgery and surgical repair of a detached retina are two examples of eye surgery.

- Age-related macular degeneration Diabetes

- blockage of retinal veins (e.g., retinal vein occlusion)

- ocular inflammation

- damage to the eye

- adverse drug reactions

Pathogenesis: Etiology

Inflammatory conditions of the eye

In uveitis, CME’s precise pathophysiology is yet unknown. When too much fluid gathers inside the macular retina, CME occurs. This is hypothesized to happen once the blood-retinal barrier is disturbed (BRB). Fluorescein angiography in a healthy eye clearly shows an intact barrier since the dye does not seep into the retinal tissues and remains inside blood vessels. Particularly, there is no dye egress from the avascular region at the macula, which stays black. Fluid swells both intracellularly and extracellularly in the retina when the BRB is injured (Yanoff et al 1984).

Accumulation of extracellular fluid impairs retinal architecture and cell function. It is believed that Müller cells play a significant part in maintaining the macula’s dehydration by serving as metabolic pumps. However, CME may also result in intracellular fluid buildup in the Müller cells, which would further impair macular retinal function. Hirokawa and colleagues’ (1985) findings, which revealed that uveitic eyes with total vitreous detachment are likely to have fewer macular alterations than those eyes without complete vitreous detachment, suggest that vitreous traction may also be at play.

It is believed that cytokines including interferon, interleukin-2, interleukin-10, and tumor necrosis factor are crucial participants in the production of intraocular inflammation since they have been found in both the intraocular fluids of inflamed eyes and the biopsies of the affected ocular tissue (Wakefield and Lloyd 1992). Other inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins and chemokines, are also significant inflammatory mediators in the eye and are released by a range of cell types implicated in ocular inflammation. The initiation of the inflammatory process in experimental models of uveitis is connected to the inflow of T-cell lymphocytes, notably of the CD4+ subtype, even though the causes of the majority of human types of uveitis remain unclear (Lightman and Chan 1990).

CME and Pars Planitis

The most common and significant side effects of pars planitis are macular edema and subsequent vision loss (Henderly et al 1986). Chronic macular alterations, with a permanent impairment of central vision, result from persistent macular edema for greater than 6 to 9 months; the severity of the changes is reflected in the degree of the impairment. Though not always, the presence of the pars plana exudates or membrane is more frequently linked to CME and more severe vitreous inflammation (Henderly et al 1987).

HIV, Uveitis, and immune Recovery CME

CME is infrequently seen in this clinical scenario, despite the fact that serous macular exudation has been recorded in individuals with AIDS-related CMV retinitis (Cassoux et al 1999). However, the incidence and prognosis of CME-related CMV retinitis have significantly improved after the advent of HAART. Some patients’ return to immunological competence is accompanied by anterior segment and vitreous inflammatory responses, which can lead to long-term problems that can be life-threatening, such as CME (Cassoux et al 1999; Holland GN 1999; Kersten et al 1999). Acute anterior uveitis linked with HLA-B27, sarcoidosis, birdshot retinochoroidopathy, Behcet’s syndrome, toxoplasmosis, Eales’ disease, idiopathic vitritis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, and scleritis are other inflammatory diseases in which CME may manifest (Camras et al 1999; Dana et al 1996; Dodds et al 1999; Helm et al 1997; Schlaegel and Weber 1984).

Macular edema with cystoid development after surgery

Irvine first described cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in 1953; this condition is now known as the Irvine-Gass syndrome (Irvine 1953).

Angiographically verified CME occurs in around 20% of individuals who have simple phacoemulsification or extracapsular extraction (Peterson et al 1992; Jampol et al 1984). Only 1% of these eyes experience a clinically significant decline in visual acuity, though (Bergman and Laatikainen 1994). There is a considerably increased incidence (up to 20%) of clinically visible CME following cataract extraction if there is posterior capsule rupture and vitreous loss, extensive iris damage, or vitreous tension at the site.

This higher incidence is unrelated to the use of an AC-IOL (Bradford et al 1988). Clinically significant CME often appears 3 to 12 weeks following surgery, although it is possible for it to take months or even years for it to start. In 80% of patients, spontaneous resolution of the CME and subsequent visual improvement may take place within 3-12 months (Bonnet 1995).

A poor functional visual outcome from cataract surgery in diabetic individuals may be caused by a rapid acceleration of pre-existing diabetic macular edema. If the severity of the retinopathy is diagnosed beforehand and promptly treated with laser photocoagulation, either before surgery, if there is a sufficient fundal view, or immediately after, this can be avoided (Flanagan 1993).

In a prospective clinical and angiographic investigation, Dowler and colleagues (1999) found that macular edema spontaneously resolved in 69% of the eyes where clinically significant macular edema developed in the first six months following cataract surgery. In contrast, if macular edema had been present at the time of surgery, it remained in every eye. Studies comparing extracapsular cataract extraction with phacoemulsification for diabetic patients have shown no difference in the prevalence of postoperative clinically significant macular edema, highlighting the need for early intervention when necessary over surgical method choice (Dowler et al 2000).

Tolentino and Schepes supported Irvine’s (1953) first description of the vitreous’ etiologic involvement in aphakic CME (ACME) as a complication of vitreous traction (1965). Gass and Norton (1966) questioned the real etiology of vitreomacular traction, but Reese and colleagues (1967) expanded on this theory by proposing that, after cataract removal, vitreous traction happened as a result of vitreous loss or delayed rupture of the anterior vitreous face.

Histopathology has supported the idea that vitreomacular traction results in CME (Wolter 1981). Several writers have suggested a link between the anterior vitreous face rupture and the development of ACME (Hitchings 1977; Irvine et al 1971). ACME has been linked to other anterior segment alterations, such as the imprisonment of the anterior vitreous to the corneal incision. This consequence is linked to a lower functional outcome as well as a higher incidence of ACME (Federman et al 1980).

Eye vascular conditions

Diabetic eye edema

Diabetic macular edema is one of the most typical causes of visual loss in people with diabetes (DME). Within the macula, cystic alterations that signify the localized coalescence of exudative fluid may be seen.

The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) clearly characterized the kind of DME known as clinically significant macular edema (CSME) (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group 1985, 1987). If any of the following conditions are satisfied, CSME exists:

- Any thickening of the retina 500 m or less from the foveal center.

- Hard exudates that are 500 millimeters or less from the foveal center and connected to nearby retinal thickening (which may extend beyond 500 millimeters)

- Any portion of a 1-disc-area-or-larger region of retinal thickening that is situated inside the foveal center.

The hydrodynamic laws Starling’s law and LaPlace’s law regulate the mechanics of diabetic macular edema (Gardner et al 2002). According to Starling’s law, the interaction between lumenal hydrostatic pressure, which pushes fluid out of the vessel, and plasma colloid osmotic pressure, which pulls fluid into the vessel, determines the net flow of fluid and molecules across the vessel wall. Due in part to concurrent systemic hypertension and in part to the rise in hydrostatic pressure brought on by localized retinal hypoxia, the lumenal hydrostatic pressure is frequently elevated in diabetic eyes. This raises the possibility of developing macular edema and favors the outflow of fluid from arteries. According to LaPlace’s law, a vessel will expand and become more tortuous in response to an increase in lumenal hydrostatic pressure. Tight connections between endothelial cells may therefore be damaged, which would again promote fluid outflow and macular edema.

A retinal vein blockage

Another typical retinal vascular cause of CME is retinal vein blockages. CME is a significant contributor to vision loss in individuals with central retinal vein occlusion or a tributary branch blockage affecting the macula. If the edema is severe or long-lasting (lasting more than eight months), the visual components’ intercellular connections are disrupted, which results in irreversible eyesight loss (Coscas and Gaudric 1984). Compared to perfused CME, ischemic CME with branch retinal vein blockage is frequently transitory and has a better prognosis for visual acuity.

Symptoms

Diminished or blurred center vision (the disorder does not affect peripheral or side-vision)

The aforementioned symptom may not always indicate cystoid macular edema. But if you develop this symptom, see your eye doctor right away for a thorough examination.

Risk Elements

Approximately 1-3% of patients who undergo cataract removals will have reduced vision as a result of CME, often a few weeks following surgery. There is a higher chance (up to 50%) that the condition will also affect the other eye if it first manifests in one. Fortunately, with monitoring or therapy, the majority of people regain their eyesight.

Drugs and Cystoid Macular Degeneration Treatment

Effective therapy will vary since there are several potential causes of CME. Your ophthalmologist may try a variety of treatments once the diagnosis has been made and verified. Anti-inflammatory drugs like corticosteroids are frequently used to treat retinal inflammation. Although they may need to be given by injection or by mouth, they are typically supplied as eye drops. In addition to using laser surgery or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor injections, ophthalmologists can treat macular edema by administering these medicines intravenously. In some circumstances, diuretics such as acetazolamide (Diamox) may also aid in reducing the edema.

The vitreous, a substance that makes up the majority of the back of the eye, can occasionally pull on the macula and cause CME. In some circumstances, a vitrectomy (surgical to remove the vitreous gel) may be required.

The ideal course of treatment for someone with cystoid macular edema can only be advised by an eye specialist. A retina specialist may frequently be required for treatment and examination. Fortunately, if cystoid macular edema is treated, normal vision could recover.

Finding the underlying etiology of cystoid macular edema is crucial. Depending on any associated conditions, the recommended course of action may change. Treatment methods may include topical medication, periocular or intraocular injections, or both, depending on the underlying problem.

It could take some time to successfully cure the edema. Visual acuity usually becomes better. The patient should continue to see their eye doctor on a regular basis even after the edema has subsided to make sure it doesn’t return.

Conclusion

Cystoid Macular Degeneration can be caused by a variety of underlying conditions. Taking care of your general health can go a long way in preventing several of the potential causes. Regular eye exams are also of vital importance.

FAQ’s

Is cystoid macular edema the same as macular degeneration?

No, macular degeneration is a disease all of its own. Cystoid macular edema can be caused by macular degeneration as a side effect.

How dangerous is cystoid macular edema?

The macula may occasionally become fluid-filled, which will result in patterns resembling cysts. Cystoid macular edema is the medical term for it. Although there is no risk of death from this disorder, vision loss can have an impact on a person’s quality of life.

Do any vitamins cause cystoid macular edema?

Niacin, generally known as vitamin B3, is available in prescription and over-the-counter versions for decreasing hyperlipidemia or cholesterol. It can cause a rare severe response is known as niacin-induced cystoid maculopathy, a kind of retinal edema.