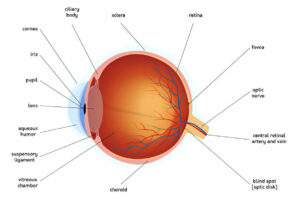

Ophthalmic examination typically reveals small white-yellow lesions in both retina and choroid, and fluorescein angiography typically shows early leakage followed by late pooling of fluorescein into active lesion areas.

CSC (Central Serous Chorioretinopathy) is an eye condition associated with leakage and hyperpermeability of choroidal vessels. Additionally, scleral thickness has been identified as an independent risk factor for CSC.

Symptoms

Choroidopathy symptoms result from fluid leakage from blood vessels underneath the retina – the back part of the eye that transmits sight information back to the brain. Leakage typically occurs through thickened and dilaated veins in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (CSC).

CSC is an autosomal dominant disorder that most often affects those between 45 and 60 years old, though anyone can be affected. While its cause remains unknown, stress appears to be an influential factor as well as use of steroids drugs.

Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy, often referred to by its popular moniker “birdshot retinochoroidopathy”, involves a progressive spread of white, fibrous lesions in both retina and choroid that coalesce into large areas of subretinal fibrosis, similar to shot marks from a gun, that form clustered lesions with white centers in between them, that appear similar to birdshot. This condition results in severe, progressive inflammation involving both choroid and retina; eventually leading to vision loss or complete blindness.

Blurred vision is one of the primary symptoms of this condition, while other symptoms may include floaters, metamorphopsia or paracentral scotoma. Uveitis can be difficult to diagnose without professional guidance from an ophthalmologist.

Flourescein angiography uses a special dye and camera to examine blood flow in the back layers of the eye. If you suffer from multifocal choroidopathy (MFC), fluorescent spots on an angiography test may help your doctor identify whether it is caused by MFC itself or another condition like primary intraocular B-cell lymphoma, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis or lupus choroidopathy.

If you have been diagnosed with punctate inner choroidopathy, PIC Society offers an online support group where you can meet others affected by this condition. Meeting monthly via Zoom on the first Wednesday of each month – find out more here – you may also wish to consider joining groups dedicated to other forms of macular disease, including Best’s Disease, RP, diabetic macular oedema as well as those who have undergone vitrectomy procedures or any choroidal neovascularization procedures such as Best’s Disease/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/RP/DRWV etc.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing choroidopathy typically relies on clinical evaluation and confirmed with imaging techniques such as fluorescein angiography – using special dye and camera, this test assesses blood flow through the back layers of the eye to show leakage from choroid tissue. Indocyanine green angiography and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) may also prove useful diagnostic tools.

Acute central serous chorioretinopathy (ACSC) is characterized by leakage from the choroid that resembles smokestack or inkblot leakage, and may lead to metamorphopsia and paracentral scotoma. Leakage fluid typically pools at the center of retina; often accompanying it is macular hemorrhage or macular edema.

Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy typically presents slowly, with progressive subretinal fibrosis and detachment of retina. Typical symptoms include blurred vision and dilated pupil (ptosis). Lesions found in this condition range from creamy white to yellow in appearance and spread across the fundus like buckshot from a shotgun, earning this disease its clinical name of birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Birdshot may be difficult to differentiate from other posterior uveitis entities and may be linked with systemic illnesses like sarcoidosis, sympathetic ophthalmia or Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome – making diagnosis often challenging despite all evidence presented of birdshot retinochoroidopathy being present.

Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy is an uncommon, idiopathic inflammatory condition of the inner choroid and outer retina that usually manifests itself among young adults, and predisposes myopic females in particular. Triggered by stress or trauma, its symptoms typically remain localized to peripheral areas at first; but may eventually progress into macula. Ophthalmoscopic findings include white-to-yellow lesions with raised borders (Figures 1a&b) with elevated macular elevation.

Diagnosis of Lupus Choroidopathy is made based on characteristic ophthalmic examination and history, including prior treatment with systemic Lupus Erythematosus medication; laboratory testing typically is unrevealing. Since 1968, 28 cases of Lupus Choroidopathy have been documented; each affected choroid displays severe chronic vitreous inflammation with white, fibrous subretinal lesions that cohere across most of retina and choroid in a progressive fashion; visual acuity usually improves with treatment regimen. In most patients visual acuity improves with therapy alone.

Treatment

Choroidopathy has improved substantially with new treatment models. Intravitreal anti-VEGF pharmacotherapy has taken its place as the mainstay treatment for central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR), decreasing macular thickness and improving visual acuity for many exudative AMD patients while simultaneously decreasing macular thickness and improving visual acuity. Depth imaging optical coherence tomography helps ensure accurate monitoring of disease response.

Choroidal neovascularization has many causes; various pathological processes, including myopia, aging, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, viral eye infections, retinal pigment epithelium diseases and others can contribute to its formation.

Inflammatory choroidal neovascularization can be identified based on several characteristic ophthalmic findings, including an increase in blind spot size, distortion of central vision and blurring vision. It often shows up alongside family history of autoimmune eye disease. Diagnostic tests such as fluorescein angiography can show evidence of leakage of fluid into retina which indicates presence of choroidal neovascularization.

Treatment for inflammatory choroidal neovascularization often includes intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy administered via injection or gel implant, usually with rapid vision restoration following rapid reversal; studies indicate the long-term benefits are comparable with laser photocoagulation.

Progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome is an uncommon disease characterized by white, fibrous lesions that ultimately form into an envelope encasing both the choroid and retina. While its cause remains unknown, recent studies indicate it could be related to latent tuberculosis infection.

Other inflammatory choroidal conditions, including serpiginous choroiditis, sarcoid posterior uveitis and birdshot retinochoroidopathy may be treated with steroids and other anti-inflammatory agents; others, like Uveitis associated with Behcet’s disease may need immune suppression medications instead. Choroidal neovascularization patients usually respond well to treatment; frequent examinations should be scheduled. Patients should also be counseled regarding risk of additional ocular and systemic problems (including cardiovascular disease), as well as evaluation and therapy as necessary.

Prevention

Research is ongoing into the causes of choroidal leakage and hyperpermeability in central serous choroidopathy (CSC). It is thought that such leakage and hyperpermeability contribute to CSC by increasing hydrostatic pressure within choroidal tissues – this pressure may lead to thickening of vasculature as well as formation of a choroidal neovascular membrane.

Reportedly, a 38-year-old woman with punctate inner choroidopathy experienced a recurrence of choroidal neovascular retinal membrane 8 months after starting on thalidomide therapy for this condition. Thalidomeide therapy only moderately reduced this patient’s choroidal neovascular membrane’s return, suggesting it may only be moderately effective at preventing future episodes. Choroidopathy typically resolves on its own over time; however treatment should be recommended if severe leakage or vision loss occurs.